Future Artist-Maker Labs

In 2016 I was selected as the artist representing Northern Ireland for the European Future Artist-Maker Labs. I would complete an international residency in Madrid working with Ultralab and Medialab Prado. The above images document the results of my investigations as they were eventually exhibited and the images below show the processes that created these assemblages.

In preparation for my residency in Madrid I was fortunate to be allowed access to the Derry~Londonderry FabLab's Bootcamp for Artists program where I could familiarise myself with the machines and processes of digital fabrication. Through my own processes of researching, making, failing, and conversing with the awesome staff there I eventually narrowed the focus on my investigation. I would explore how bioprinting—positioning biological materials bodily repairs across space and time are altering what it means to be human.

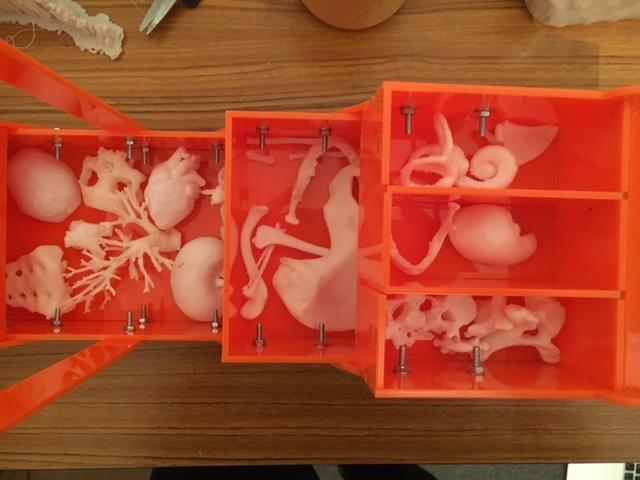

Retrofit [prototype] (bioFila filament, laser-cut acrylic)

After much experimenting I settled for bioFila Linen, an interesting new biodegradable product from the company, twoBEars in Germany. BioFila Linen does not actually contain linen fibers as is customary in many other PLA based materials. Rather, bioFila Linen is composed of organic material known as lignins that are suspended in a PLA matrix. Lignins are responsible for providing strength and rigidity to the cell walls of plants and are one of the main ingredients found in paper. 3D printed bioFila Linen has a texture that looks a lot like linen (hence its name) and, according to twoBEars, is capable of producing rougher, more porous-looking textures at temperatures above 205°C.

No Donor Required (bioFila filament, latex tubing, IV stand)

This major strand of my artistic investigations considered the retro-fit approach of bioprinted laboratory grown material being matched to an existing body to enable and support natural growth process around implanted parts. Bioprinting creates biomaterial that mimics human body tissue. It involves the use of ‘bioink’, or living cells that have been cultured in a cell growth medium. The bioink is loaded into a cartridge, inserted into the bioprinter and layers of this material are laid down on sterile surfaces with the guidance of software to form new biological materials. Depending on what is being fabricated, a form of scaffolding may be used to help shape the object. One ultimate aim of bioprinting is to generate new human tissues and organs, such as hearts, livers and kidneys, for use in transplants and grafts. Current uses of bioprinting include the production of material for medical education. This material allows students to cut through or dissect the tissue as part of their surgical training. Researchers are working on bioprinting human tissue that will be capable of developing full biological functions for use in testing dangerous or experimental drugs.

Some of these developments offer a further step towards ‘personalised medicine’ that began with genetic testing and the customisation of medical treatment based on a patient’s genetic makeup . It has been speculated that 3D printed biomatter could be created that is a genetic match to individual patients and could then be used to test treatments before using them directly on patients themselves.

The Modern Prometheus etching (laser-cut acrylic and card)

Bruno Latour notes that the name of the scientist in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, is commonly mistakenly assigned to the monster he creates. He suggests that perhaps the monster is actually Dr Frankenstein, not because of what he created but because, “he abandoned the creature to itself” (Latour 2012). Through this anecdote Latour suggests that we are implicated in the manifestations of monstrous technologies when we disengage from the consequences of what has been created.

During the many hours that I spent printing these human bodily parts I thought I would familiarise myself with the Frankenstein story, conveniently now freely available in audiobook format on youtube. Certain sentences resonated with me. I logged the position of these sentences and later retrieved them, mashed them together using Audacity and exported the following audio file:

I cut these audio files on an Epilog 120 Watt Legend EXT to a theoretical precision of 1200dpi (the kerf of the cut and some tricks I used to avoid crashing the laser cutter dropped the actual precision down by ~1/6). The audio on the records has a bit depth between 4-5 (typical mp3 audio is 16 bit) and a sampling rate up to about 4.5kHz (mp3 is 44.1kHz). Since I couldn't control the power of the laser while it is cutting a vector path, the laser cut records are cut laterally on the surface of the material. This means that the needle only vibrated in the plane parallel to platter of the turntable. The laser cutter couldn't make such precise cuts because the width of the beam is too large, so the grooves on my records were about 1-2 orders of magnitude larger in every dimension than these grooves.

Loading/Uploading, nothing's ever waste (bioFila filament deposits on acrylic)

Currently, finished products are the focus of knowledge sharing in the maker movement and are often presented as a kind of recipe for others to reproduce. In this model, the processes of working that gave rise to the idea for that product or its successful implementation are obscured. Critical making important role of open-ended and emergent approaches to making indeterminacy and resistance play in interactions, unpredictability versus process-driven values of consistency, precision, and accuracy.

Hand Printing (bioFila filament nest on acrylic)

As I grew more comfortable with the 3D printers that I was working with—towards the end I was juggling four printers—I started to interfer with the output of the machines not automatically using code but manually using my hands to guide the positioning of what was extruded. Apart from a few inevitable burns (the extruder is very hot) I enjoyed a more free flowing interaction with the machines.

Empowerment is not about the ability to realize one’s existing ideas, instead, it stems from the ability to listen and respond to materials as they take on forms. This maker is a performer among a cast of human and nonhuman counterparts, organizing her actions in relation to the others to form critical inquiries into the world. While the machines, materials, and outcomes may look similar to other acts of making, the way this maker goes about doing making may be better understood as improvisation, interplay, and the entangled performance, rather than as predetermination, domination, and control.

All that remains (scaffold of pulonary artery file Glowfill filament, acrylic mirror)

(scaffold of pulmonary artery file 3D printed in Glowfill filament, acrylic mirror)In experimenting with the dual extruder, I wanted to make explicit the invisible supporting structures these creations. So I decided to only print the scaffolding and not load any filament into the primary extruder. So I was effectively highlighting the void - the space in-between.

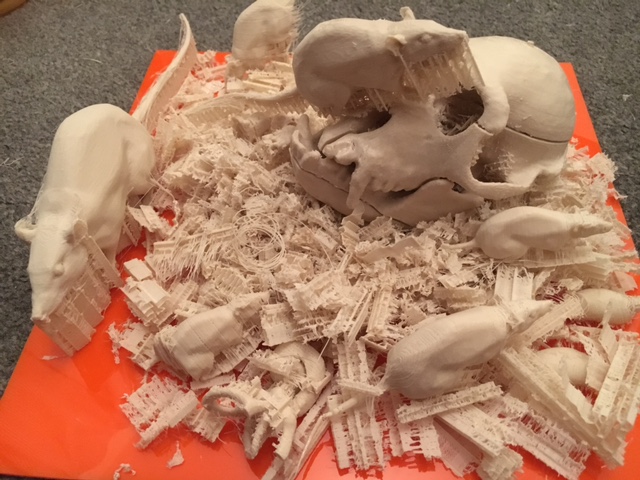

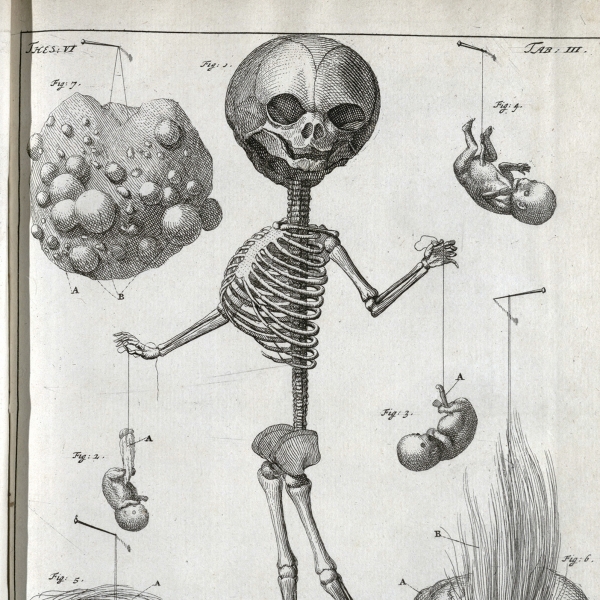

Thesaurus Anatomicus recut (laser-cut plywood)

On a trip to St Petersburg in 1999 I cam across the work of Frederik Ruysch. He was a Dutch Anatomist born in the 17th century who created surreal amalgamations of botanical, animal, and human anatomical specimens. Tsar Peter the Great of Russia had transferred the collection to St Petersburg in 1717. Ruysch created still lifes, illustrated from careful preparations of his own invention. For example, by heating a white wax and injecting it into the circulatory system of his specimens, he was able to make them malleable and poseable. Detailed etchings of his tableauxs were captured in the Thesaurus Anatomicus which I browsing through thinking about how the human bodily parts have been represented in art. Two of these images of his dioramas resonated with me. One was a human fetus with a grossly enlarged head lovingly grasps a portion of its own placenta. The other was an image of three fetal skeletons seem to frolic and dance amid a gall bladder coral with vascular trees .

Mark leaving Lenses (found photographic print wit laser lens burns)

On my daily walk to Ultralab and Medialab I would pass the antique district of La Latina. One particular shop drew me in. Always open with its contents spilling onto the street, it was far from the other tourist traps surrounding it. I found the photograph above. It had a stamp on the front of a photographic studio from the city of Zaragoza, Photoelectra. The print showed the a man looking beyond the lens. He was decorated with a medal attached to a ribbon around his neck and another pinned to his chest.

I often like to use found materials to situate my work within the broader historical context. For this piece I wanted to refer to other lens based technologies; those mark making lenses. I thought of photography and its emergence in the mid nineteenth century accompanied by claims of the democratisation and expansion of the privileges of honorific portraiture beyond the bourgeois. This period also saw photography accepted as one of the most objective means for recording scientific data, - when quantification and interpretive techniques were being used to measure the human body: from Taylor’s time and motion studies to, and eventually anthropo-metry (measuring human physical variation, in an attempt to correlate physical with racial and psychological traits). - the attempt to classify the criminal body- the anthropometric system of physical measurement identification and full face and profile photographs, claiming that judicial photographic documentation of the body of the criminal would enable the visualisation of biotypes that could further define deviant bodies within society.

I decided to experiment with retraining the lens of the . An agential realism approach recognises practices of making as boundary-making. In this example of laser cutting and its associated production of borders, the lens dictates “what matters and what is excluded from mattering” (Barad 2007, p. 148). This process saw my material engagement with the machine choosing parameters and positioning the print. This was a process involving cuts, cuts that do violence. They open up and rework the agential conditions of possibility.

Moveable Type (laser-cut paperback books)

Through the residency, in exploring the revolutionary potential of CNC making in light of past technical innovations, I starting thinking about revolutions in printing. this lead me to consider the moveable type printing press. I wanted to reference the parallels between this technology and the rhetoric surround the potential of laser cutter to transform our lives. I decided to experiment with chance to access type from a text, paperback novels I found in the antique shop where I had found the photograph.

The stuff of Additivism (BioFila, Glowfill, and abs filaments, test-tubes, laser-cute acrylic test-tube holders)

Following the residency I am left wondering how to acknowledge the web of bodies that made this work possible. While I figure this out I can only pay gratitude to those Thingaverse and Instructables contributors who generously made their files available for use as well as those owners of the body parts that these files were based on. The FabLab Northern Ireland team, particularly Steven and Kerry in Belfast, and Declan, Paul and Rachel in Derry who helped my ideas manifest both before and after the residency. And particular thanks go to Gustavo, Violeta and Elio at Ultralab, and Javier and Daniel at Medialab Prado for enabling my explorations to be so supported and fruitful.